Runners from Kenya have been responsible for numerous marathon world records in recent decades.

For example, between 2003 and 2023, six Kenyans ran new world records in the marathon. Ethiopian Haile Gebrselassie was the only non-Kenyan to also set one (or even two) marathon world records during this period. Reason enough to take a closer look at the training of the Kenyans and also their neighbors from Ethiopia.

But besides the training itself, there are other reasons that explain the incredible dominance of African athletes in running.

Training at an altitude of over 2,000 meters

Both Kenyans and Ethiopians have a huge advantage over a large area of competition from Europe or other continents. The "training centers" of the marathon pros are all located in the highlands at an altitude of over 2,000 meters. In Kenya, this is the town of Iten. This is at an altitude of 2,400 meters. Almost all Kenyans who want to build up the potential to become world-class runners live here or in the large city of Eldoret, 25 meters away. Eldoret is also about 2,000 meters above sea level.

Ethiopia's counterpart to Iten and Eldoret is Addis Ababa. Like Iten, the capital of Ethiopia is located at an altitude of about 2,400 meters. The region around Addis Ababa is the hotsport of many top Ethiopian runners. Many world-class runners can also be found in the small town of Bekoji at an altitude of 2,500 meters. Among others, the Olympic champions Tiruensh Dibaba and Kenenisa Bekele grew up here.

Life at altitude is a great advantage

All these training sites have one thing in common. They are located at altitudes well above 2,000 meters. While Europeans regularly visit these regions for three- to six-week training camps, Africa's professionals train in Africa for most of the year. They only leave their home country for international competitions. And that could be one of the big advantages. After all, major city marathons or international championship races are usually held at a much lower altitude.

The effect of altitude training explained

At 2,500 meters, the oxygen content is just as high as in the lowlands, but the air pressure and the partial pressure of oxygen are reduced at altitudes above 2,000 meters. At 5,500 meters, the air pressure is reduced by half; above 2,000 meters, the air pressure is about 75-80% compared to sea level. This reduced air pressure leads to a lower oxygen partial pressure (=SpO2) and a reduced amount of oxygen that can be absorbed by breathing. The result is a lower oxygen saturation in the blood.

Acclimatization

If one is not used to the altitude, this process initially leads to slight drops in performance. Over time, however, the body becomes accustomed to these conditions. In this case, one speaks of acclimatization. Due to the lack of oxygen in the tissues, however, the body has to work harder to supply the blood or the cells with oxygen. Since the body has to adapt to these conditions, the body adjusts accordingly by increasing the heart rate and breathing rate. This results in improved respiratory minute volume. But the most important result of this whole process is an increased red blood cell count. This allows the body to carry more oxygen to the muscles. The result is improved endurance performance. Read more here: Effect of altitude training

Many endurance athletes therefore do their pre-season training camps at high altitudes to simulate exactly the process described above. Africa's athletes benefit from this throughout their lives. In addition, for these athletes, a marathon in cities like Berlin, London or New York feels much less stressful than their training at an altitude of over 2,000 meters. On the other hand, runners who train mostly in the lowlands do not feel any better in competition than they do when training at the same level.

Little asphalt, lots of cross

While most European runners are unlucky in terms of altitude compared to Africans, many other training details of the world's best runners can be copied.

For example, there is the surface of the training courses. Eliud Kipchoge, Kelvin Kiptum, Kenenisa Bekele & Co do most of their running training on profiled and unpaved tracks. This applies above all to all basic runs, but also to more demanding units such as the driving game (more on this below). Even the long endurance run in marathon training is mostly run on gravel surfaces and selective courses. Only for tempo runs, such as interval training, are the conditions optimized, but nowhere near as optimized as in Europe. The 400-meter tracks in Kenya or Ethiopia are usually not in as good condition as in Europe, for example.

This somewhat lower training comfort also hardens additionally and provides advantages in the competition under optimal track conditions compared to runners who have trained mainly on the flat and on asphalt.

High volume for the marathon

World-class marathon runners sometimes achieve distances of over 200 kilometers per week in their training preparation. In most cases, one or two "short" base runs of up to 20 kilometers are completed every other day. In between, there are the core units of interval training, driving game and long endurance run.

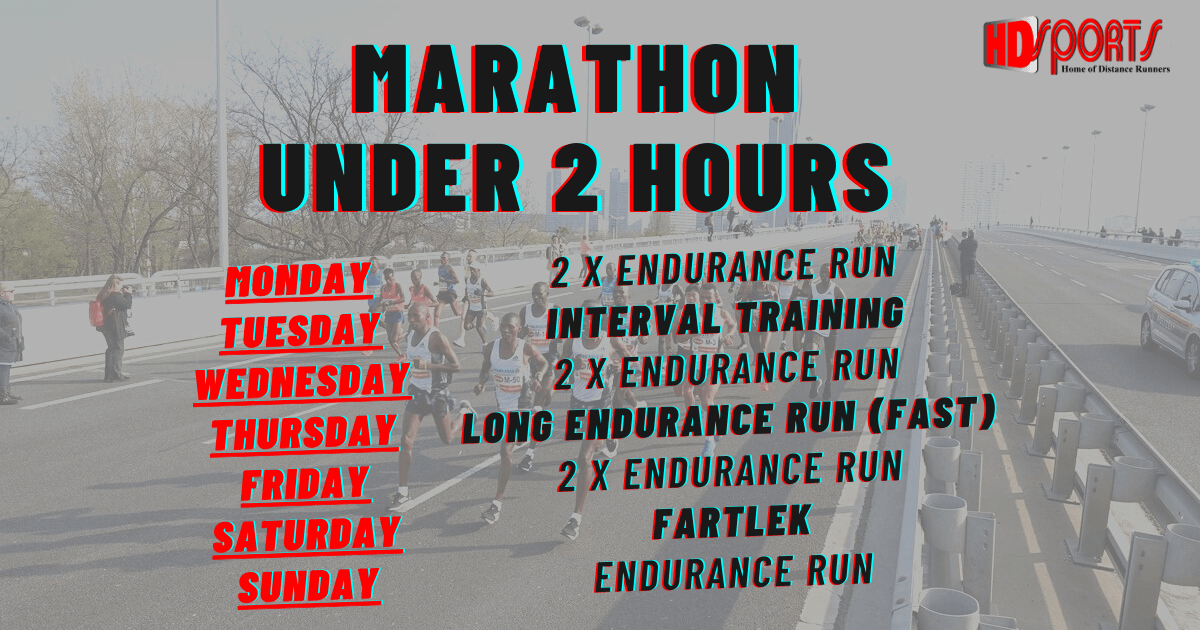

Eliud Kipchoge, for example, trained for his marathon in under 2 hours primarily as follows:

- Monday: 2 base runs (1 x up to 21 km, 1 x up to 12 km)

- Tuesday: interval training

- Wednesday: 2 base runs (like Monday)

- Thursday: Long tempo endurance run (NOT slow - more on this below)

- Friday: 2 base runs (like Monday)

- Saturday: Driving game. Alternatively, another short basics run in the afternoon with sufficient energy

- Sunday: 1 base run (around 20 km)

In total, Eliud Kipchoge covers around 200 kilometers per week: How Eliud Kipchoge trained for the first marathon in under 2 hours!

The long endurance run is NOT run slowly

This advice will also be valuable for many amateur runners. Because the often erroneous recommendation to run the long endurance run in marathon training as slowly as possible is not shared by Africa's runners at all. The long endurance run should be run at least in the basic range 1 (65 - 80% of maximum heart rate).

The distance varies between 30 and 40 kilometers, for the less well trained also shorter or a maximum of slightly more than 30 kilometers. There is no point in running significantly longer in training than planned for the competition. And if you run significantly slower in training than the planned marathon pace, then exactly this problem occurs. Basically, even for hobby runners, long endurance runs should not exceed a period of 3 hours.

The pace: The first 2 - 3 kilometers very easy, then increase at least to the basic pace. Kipchoge ran a pace of 2:50 minutes per kilometer in his 2019 marathon (1:59:40 hours). From kilometer 3 on, he comes to a pace of 3:00 - 3:25 minutes per kilometer during the long training run, strongly depending on the course, because it is constantly slightly uphill and downhill. In the hilly part he comes to 3:15 - 3:20 minutes per kilometer, in the flat he increases the pace to 3:00 minutes per kilometer. In the end, the average pace is only 20 to 25 seconds above the marathon pace.

Fartlek

Among amateur runners, the Fartlek is very rarely used. African runners, however, swear by this unit, not only in seasonal preparation, but also in specific preparation for a marathon.

In the Fartlek, there is an alternation of high speed and basic speed (no leisurely trotting). In contrast to interval training, however, there are no exact pace specifications for the fast runs, especially since the driving game is also run on profiled terrain. For the most part, however, the pace for the fast runs is in the range of the marathon pace or slightly faster.

Interval training: At least 1 time per week

Of course, nothing works for Africa's top runners without interval training. Next to the driving game, it is the second tempo unit of the week, but with a higher load.

Interval training involves an alternation of high load and recovery (trotting). The fast runs are run at least at competition pace, but mostly a little faster, depending on the interval training planned.

Interval sessions are also mostly done on the track by Africa's top runners. It is the only training that takes place entirely on a flat track. It is not run to maximum exhaustion.

Low complex, but efficient nutrition

While our society is stuck in the low carb trend, the professionals from Africa continue to rely on high carbohydrate diets. The favorite food of many is ugali. A rather "boring" dish made of cornmeal and water, but it provides an incredible amount of carbohydrates and is well tolerated.

Athletes like to get protein from legumes, poultry and beans. Sugar must not be missing from the menu either. Many teaspoons of sugar are added to the popular chai tea.

Plenty of sleep

"Train, Eat, Sleep, Repeat" - this wisdom is embodied by runners from Africa. There are no distractions. In the training area where the athletes live in preparation for their competitions, there is even gender segregation. So spouses are forbidden. There are no other distractions either. While many top athletes in Europe or America study or pursue other sideline activities in addition to their sport, athletes in Kenya and Ethiopia devote themselves primarily to regeneration. They also avoid the temptation of social networks.

They should get at least 8 hours of sleep a night, plus a short "power nap" during the day between sessions.

Lifestyle and schooling

In addition to the Africans' lifestyle, which is 100 percent focused on running, most of the top international stars have already built their foundations in early childhood. There are interesting stories from many world record holders about their daily runs to and from school.

The best-known example is probably Ethiopian Haile Gebrselassie. As a child, the two-time Olympic champion and two-time marathon world record holder ran ten kilometers to school every day in the morning and the same distance home again in the afternoon. In doing so, Gebrselassie had built up a basic endurance that a European child with the typical European lifestyle (bus to school and little sports offered in schools) can never catch up on.

More Marathon:

Kommentar schreiben